The Koni-class frigate Al-Hani (F-212), long considered the flagship of the Libyan Navy, has returned to the Abu Seta naval base in Tripoli on October 23, 2025, following a technical overhaul and maintenance period exceeding a decade in Malta.

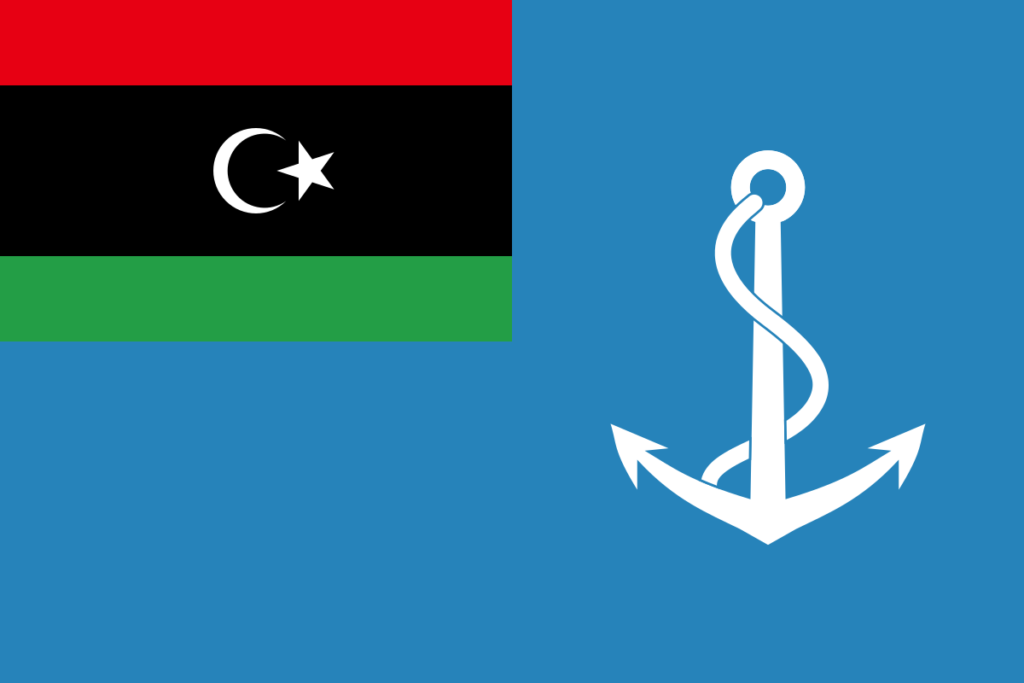

This development represents a significant political and institutional success for the country’s centralized authority, the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA). The frigate’s repatriation is presented as a concrete step in the Libyan Ministry of Defence’s long-term plan to re-establish the national military inventory.

A Symbolic Victory After a Twelve-Year Standoff

The Soviet-built Project 1159TR Koni-class Al-Hani was commissioned in 1985 and became the largest surface combatant in the Libyan Navy. With a displacement of approximately 1,900 tons and a length of 95 meters, the platform was historically designed for coastal surveillance and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) missions.

The decision to send the frigate abroad for maintenance around 2013 1 and the ensuing twelve-year delay in its return were direct consequences of Libya’s political fragmentation and international sanctions. This prolonged custody indicates a significant financial and diplomatic success for the Tripoli government, which was finally able to settle the extensive shipyard debts and overcome the international political hurdles necessary for the asset’s return.

The Ministry of Defence stressed that this step is part of its plan to “rehabilitate and retrieve naval vessels, aircraft, and military equipment located abroad” and reinforce operational readiness.

UN Constraints: From Warship to Patrol Platform

While the Al-Hani‘s return carries immense symbolic weight, its operational capabilities remain under strict international oversight. The vessel is subject to the UN arms embargo in place since 2011.

This requirement severely limits the vessel’s combat capacity. The UN Panel of Experts on Libya visited the vessel in Malta in April 2019 to inspect its weapons systems and assess their “potential effectiveness,” subsequently providing recommendations for demilitarization before its return to Libya. This implies that the ship’s primary weapon systems—such as the P-15M Termit anti-ship missiles and RBU-6000 ASW systems—have either been disabled or removed to ensure compliance with the embargo.

Consequently, the Al-Hani‘s core function has shifted from a heavy warship to a large surveillance and patrol platform, enabling the GNA to project maritime sovereignty. The frigate’s size and sensor capabilities are crucial for monitoring and combating illicit activities, particularly the widespread illegal fuel smuggling operations along the country’s western coasts.

Logistical Challenges and Future Outlook

Although the Al-Hani‘s repatriation provides a military boost to the Tripoli authorities, long-term challenges persist. The vessel is an aging Soviet-era design, approaching forty years of service. Maintaining such a platform requires sophisticated training, a steady supply of spare parts, and specialized foreign technical support, all of which strain the logistical capabilities and budget of a fractured state.

Significantly, the Al-Hani‘s sister ship, Al Ghardabia (F-213), remains explicitly documented as “inoperational” , highlighting the logistical fragility inherent in sustaining these legacy platforms within the current Libyan naval structure. The frigate’s successful operation is a critical, yet logistically risky, first step by the Western-based authority toward re-establishing effective naval jurisdiction.